The following post was written by Barry Sackin of Sackin & Associates.

What is Child Nutrition Reauthorization?

This June will mark the 70th anniversary of the National School Lunch Act (NSLA), now named after Sen. Richard B. Russell from Georgia who is considered to be the father of the legislation. When it was first enacted, the NSLA was what is called a “grant-in-aid” for states to develop and support school lunch programs. Over the years, this approach has been replaced by the program we know today. The way it has made the changes is through regular reauthorizations, or legislation that amends the law. There have been almost two dozen reauthorizations over the past 70 years, as well as changes enacted in legislation between the regular schedule.

School breakfast and lunch are permanently authorized. That means no Congressional action is needed to keep things as they are. They also receive mandatory funding, so we are not subject to the annual appropriations process. But other parts of the NSLA and the Child Nutrition Act of 1966 (a complementary bill that includes, among other things, school breakfast) go away after a date set in the law. Without Congressional action, these sections sunset. Congress uses this deadline as an opportunity to make many changes in the basic laws governing school meals and the other programs authorized by the acts.

Traditionally, Child Nutrition Reauthorization (CNR) occurred every four years. But back in 1998, they shifted to a five year reauthorization (so that the legislation didn’t come up during election years). That year, the sunset date was set to September 30 (end of the federal fiscal year) 2003. However, the legislation got bogged down and reauthorization didn’t happen until 2004. In 2004, once again they chose a five year reauthorization so it wasn’t an issue during elections, and again, Congress failed to get the work done on schedule and the legislation was enacted in 2010. We know that bill as the Healthy, Hunger-free Kids Act of 2010 (HHFKA). Congress enacted another five year reauthorization, requiring action in 2015.

Which brings us to today – 2016. Looks like Congress missed the target date again. Without getting all technical, September 30, 2015 passed and, until Congress enacts a CNR, all provisions of current law stay in effect. That means that things school foodservice folks would like to see fixed from the HHFKA and menu planning regs have to wait … sort of. We’ll come back to this.

In the middle of January, the Senate Committee on Agriculture, Nutrition and Forestry passed out a comprehensive CNR. The 210-page bill covers all of the nutrition programs. For school foodservice professionals, there are several important issues addressed in the bill, but today we’re only going to talk about nutrition standards.

Since 1994, the NSLA has required school meals to be consistent with the Dietary Guidelines for Americans (DGA). HHFKA reinforced this requirement and shortly after passage, USDA issued updated menu planning rules for the first time in more than fifteen years. Three key requirements are causing school operators a bit of heartburn – sodium, whole grain-rich products, and required amounts of fruits and vegetables.

1. Sodium

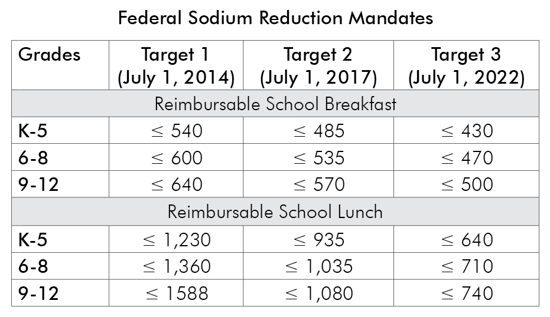

USDA rules established three targets for reducing the amount of sodium in school meals. The targets are intended to have school meals meet the DGA recommendation that average adults should consume no more than 2300 mg of sodium each day. To achieve target 3, currently scheduled to go into effect in 2022, schools will have to reduce sodium from all sources in school meals by a whopping 54% from the baseline! Even USDA in the regulations that set this says that target 3 cannot be achieved with current food and technology.

A future article will address some of the current science and thinking about sodium that may help you understand some of the issues and concerns that schools have about the menu planning requirements. But one concern is pretty obvious. Kids don’t seem to like the new, reduced sodium products, and we are only at target 1. Also, given some of the confusion and revisions we experienced in the initial roll-out of the new menu requirements that ended up costing all stakeholders a great deal, industry is hesitant to make more changes in formulations until there is certainty about what the requirements will ultimately be and whether schools will actually buy the new products.

Why is there uncertainty about where this is all going? In response to what they were hearing from constituents including SNA, for the past two years Congress used the annual appropriations process to provide schools with some flexibility regarding sodium and whole grain.

What’s the Senate bill do? Target 2 for sodium is scheduled to into effect in 2017. If enacted, the Senate bill would delay that until 2019. It also would require USDA to study current science and reconsider target 3. While the delay puts off the pain, it doesn’t provide any certainty. It also suspends target 3 pending research that won’t start until 2019. Not much relief there.

2. Whole Grain-rich

There is some confusion about what the requirement is for breads and grains. USDA has established that, for the purpose of school meals, whole grain-rich (WGR) means that half of the grain content of an item must be whole. So a slice of bread with 9 grams of grain must include at least 4½ grams of whole grain. The rest can be enriched.

The current requirement, implemented after a phase-in period, is that all bread and grain items must be whole grain-rich. Many schools have been challenged to meet this requirement for a number of reasons. Whole grain and whole grain-rich products are more expensive, frequently not as accepted by students, and not as functional as traditional items. For example, even the USDA can’t buy whole grain pasta that holds up to how schools have to prepare and hold lunch items. And for many schools, biscuits are a breakfast staple (and whole grain biscuits just don’t cut it).

The Senate bill would allow that only 80% of bread and grain items must be whole grain-rich. That would allow schools to offer traditional items one day out of five. Schools would prefer to go back to the interim step of 50% traditional and 50% WGR.

3. Fruits and Vegetables

No one disagrees that it would be great if we all ate more fruits and vegetables. The new menu planning rules increased the amount of fruits and vegetables offered at breakfast and lunch. But it went one step further, requiring that kids take at least a half cup at each meal. Many schools offer a lot more than the one cup requirements, and allow kids to take even more than that. But in a lot of schools, kids don’t want even the half cup. The result is that kids are forced to take a serving or two that they simply throw away. Fruits and vegetables are expensive, and throwing them away is truly wasteful. If there was funding to help educate kids about eating well and encouraging eating more fruits and vegetables, great. But cafeterias that have 30 seconds to interact with a student are not in a position to be the sole source of nutrition education in the school.

The Senate bill does not address the fruits and vegetables requirement. Maybe the House will.

What’s Next?

Well, in the next blog post we’ll talk about some of the other parts of the legislation. And in the next steps in CNR there are two concurrent paths. On the Senate side of the Hill, the bill that the agriculture committee passed without amendment or dissent moves to the full Senate. As of this writing, there is no schedule for when that will happen. But we know from questions we’ve received from Senate staff, that it’s out there. Whether the full Senate will simply accept the committee draft, whether the committee chair, Sen. Pat Roberts from Kansas, working with the Ranking Member, Sen. Debbie Stabenow from Michigan, will make changes requested by other senators and simply substitute it for the current bill, or whether the bill will be open to debate and amendment on the floor is unknown. We’ll have to wait and see.

On the House side, we expect a bill to be introduced in the next several weeks. From conversations with House Education and the Workforce Committee staff, we know they may include many of the same issues from the Senate, but theirs will be pretty different in approach and substance. Again, we have to wait and see.

In the near future we’ll talk about other provisions in the Senate bill including a significant change in the verification process, the House bill when it comes out, and the promised science behind the sodium standards. Please let me know if there are other issues you’d like more information on.

About the author

Barry Sackin is a school foodservice veteran of more than 35 years. Barry started his career on staff at San Diego Unified School District in 1980. Barry was a director of large districts for several years, at one point overseeing two districts with more than 70 sites and nearly 45,000 students. While serving on the SNA Board of Directors, Barry was asked to join the staff as VP of Public Policy and has since worked on child nutrition policy for the past 20 years.

Barry Sackin is a school foodservice veteran of more than 35 years. Barry started his career on staff at San Diego Unified School District in 1980. Barry was a director of large districts for several years, at one point overseeing two districts with more than 70 sites and nearly 45,000 students. While serving on the SNA Board of Directors, Barry was asked to join the staff as VP of Public Policy and has since worked on child nutrition policy for the past 20 years.